Case Study: Achieving Universal Health Coverage in Samoa

1. Overview

Samoa is a lower-middle income country with an estimated population size of 214,900.(1) As a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), Samoa is spread over 2840 km2 across nine islands and has one major urban center, Apia, located on the island of Upolu.(2) The nation faces many key health challenges including the rise of noncommunicable diseases, insufficient service capacity, and limited financial resources.(3) The government has expressed a clear commitment to achieving universal health coverage and has demonstrated this through increased government health spending.(4) However, the projected demographic changes, economic reliance on external aid, and recent political shifts have created significant constraints for the government to overcome. Samoa must rely on both traditional and innovative approaches to address its key health challenges and achieve universal health coverage.

2. Historical Overview of Health System

The development of the Samoan health system has its roots in early twentieth century colonialism. Following World War 1, the League of Nations classified Samoa as a territory of New Zealand and mandated the New Zealand government to “promote to the utmost the material and moral well-being and the social progress off the inhabitants of the territory.”(5) In the aftermath of the 1918 pandemic, the Samoa Act of 1921 was established with two primary health goals: build accessible medical services and develop preventative educational resources.(6) In the ensuing years, a collection of district hospitals, out-stations, and dispensaries were developed to offer health services to the population.(7) An annual charge of £1 per Samoan provided free treatment for all members of the population.(7) By the mid-twentieth century, health disparities between urban centers and village communities began to arise and the National Health Department established the Komiti Tumama (women’s health and hygiene committees).(8) These committees were tasked with delivering primary health care services to villages and became a key component of the health infrastructure.

Following independence in 1962, the authority of the Samoan health system shifted to local leadership and Komiti Tumamas were further integrated into villages.(9) However, over the subsequent decades, the role and value of these committees began to falter as more district hospitals and health centers were developed. In 2006, the government of Samoa divided the health system into the Ministry of Health (MOH), responsible for policy regulation, and the National Health Service (NHS), responsible for service delivery.(10) This separation resulted in rising expenditure on personnel, decline in service provisions, and reduced community health engagement.(7) In 2019, the NHS Amendment Bill, unified the National Health Service with the Ministry of Health to allow for a more cohesive and regulated approach of service delivery across the country.(11)

On October 5th, 2023, the nation of Samoa, alongside 192 UN Member States, adopted the UN Resolution on universal health coverage.(12) In adopting the resolution, Samoa committed to achieving universal health coverage by providing a full range of health services to all segments of the population without exposure to financial hardship.(12) This commitment is further contextualized by the Ministry of Health’s Health Sector Plan, “A Healthy Samoa,” which provides a framework for achieving national health benchmarks by 2030.(3) “A Healthy Samoa” details its mission as one that aims to enhance public health through people-centered care and innovative financial management.(3)

3. Structure of Healthcare Delivery System

The current structure of the Samoan healthcare delivery system is composed of public health facilities, NGOs, private sector health offices, and community-based organizations. The public sector dominates service delivery, and the Ministry of Health has been committed to achieving universal health coverage through expansion of its community-based organization PEN Fa’a Samoa. Through this program, Samoa aims to provide primary health care services to village communities and better connect individuals to public health facilities.

3.1 Public Health Facilities

The modern Samoan health system is managed by the Ministry of Health and is comprised of twelve health facilities.(8) These facilities are organized based on their ability to provide tertiary, secondary, or primary care. There are two main hospitals that offer tertiary care, the Tupua Tamasese Meaole National Hospital in Upolu and the Malietoa Tanumafili II Referral Hospital in Savai’i.(10) Tertiary health services unavailable in Samoa are referred overseas via the Overseas Treatment Scheme.(13) There are six district hospitals that offer secondary care and four community health centers that offer primary care spread evenly between the islands of Upolu and Savai’i.(10) Figure 1 provides a detailed overview of the geographic distribution of the health facilities in Samoa.

Figure 1. Geographic Distribution of Samoa Public Health Facilities (13)

3.2 NGOs and Religious Organizations

There are several NGOs and religious organizations that are engaged in service delivery and health advocacy across Samoa. The Samoa Family Health Association (SFHA) provides family planning and reproductive health services through three static clinics and two mobile clinics in Upolo and Savai’i.(14) The Samoa Red Cross is responsible for managing collection, storage and distribution of blood products in the country.(10) Nuanua o le Alofa is a national organization in Samoa that advocates for health issues for people living with disabilities.(10) The Catholic Church of Samoa Mapuifagalele Old People’s Home provides medical services for the elderly as well as conducts health promotion and prevention activities.(15)

3.3 Private Sector

There is a small private health sector in Samoa located in the urban center of Apia. The sector is mainly composed of general practitioners, allied health professionals, and pharmacies.(10) There are also an estimated 900 traditional healers (Taulasea) and 119 traditional birth attendants (Fa’atosaga) providing services in Samoa.(15)

3.4 Community Based Organizations

The historical significance of the Komiti Tumama has shaped the formation of community health organizations in Samoa. In 2015, the Ministry of Health partnered with the World Health Organization to contextualize the WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Intervantions (PEN) to form the PEN Fa’a Samoa.(8) The PEN Fa’a Samoa aims to enhance noncommunicable disease (NCD) prevention, detection, and management through active engagement with village communities.(2) It is organized through the traditional governing structure of the villages and is implemented in collaboration with the Komiti Tumama.(8) This program has been a notable success for Samoa with an estimated 90% of the population screened for NCDs.(8)

4. Health System Financing and Health Expenditures

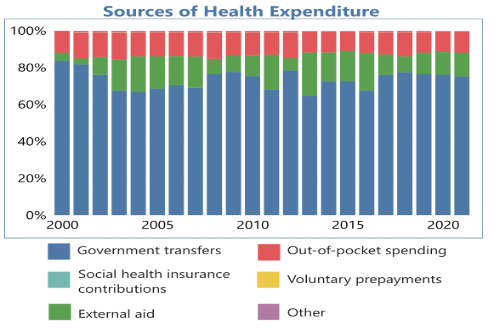

The financing of the Samoan health system reveals an inherit concern for its path toward universal health coverage. Over the past two decades there has been an increase in external aid as a source of health expenditure. This has created a reliance on external development partners for assistance and has restricted Samoa’s ability to direct its resources toward national health priorities.

4.1 Sources of Financing

Since 2000, Samoa has had a gradual increase in its health expenditure as a percentage of GDP growing from 4.3% in 2000 to 6.80% in 2020.(4) The current health expenditure is predominately financed through government spending at 75.3%, external aid at 13%, and out-of-pocket spending at 11.2%.(16) Over the past two decades, domestic government expenditure has been gradually declining while external aid has increased.(16) Figure 2 provides an overview of the trends in health expenditure sources.

Figure 2. Samoa Sources of Health Expenditure (2000-2021) (16)

4.2 Development Partners

Development partners have grown to become a major player in the health sector of Samoa. The major development partners and their respective percentage of external aid are Australia DFAT (30%), New Zealand MFAT (29%), WHO/SHSMP (26%), and UNFPA (5%).(17) Development partner funding predominately supports preventative care initiatives and hospital system administration.(17)

4.3 Insurance Coverage

All citizens can receive free or heavily subsidized healthcare services at public facilities financed by the Ministry of Health.(18) The Ministry of Health is funded through general tax revenues. The Samoan National Provident Fund is a compulsory saving scheme through age 65 in which 7% of gross monthly earnings is paid to the government.(19) This fund provides free health and medical care for citizens 65 years and over.(18)

5. Health System Constraints

5.1 Social Constraints

The Samoan health system faces a number of social constraints based on its geographic landscape and population demographics. In 2021, 82% of the Samoan population lived in rural areas.(4) These communities have a health worker density of 1 per 1,000 population, compared to urban areas’ 8.43 per 1,000 population, resulting in reduced health service access.(20) The Ministry of Health projects the Samoan population to increase 10% by 2030.(3) This has far-reaching implications on the health system as there will be both an increased demand for maternal, pediatric, and newborn services as well as elderly care and rehabilitative management. The nation also struggles to develop an adequate health workforce with a current national health density of 3.65 physicians, nurses and midwives per 1,000 population.(20) This insufficient workforce is due to issues with attraction and retention of skilled people in clinical roles. There is a high turnover rate with around 8% of health workers leaving the Ministry of Health each year.(20)

5.2 Economic Constraints

The primary economic constraints surround the limited ability of the government to finance its health system. Government health funding is financed through general tax revenue and the Samoan National Provident Fund.(18) With an average GDP per capita of $3,745 and only 6.8% of GDP committed to the current health expenditure, Samoa is unable to meet the increasing responsibilities of its health system.(4) The reliance on general tax revenue is insufficient and thus the country has become dependent on external aid to support various services. This dependency on external aid is also a major constraint to development, as the nation is unable to independently coordinate health priorities for its population.(3) For instance, the government is currently dependent on external aid to finance reproductive health services and must develop resourceful approaches to meet the growing demands faced by demographic changes.(11)

5.3 Political Constraints

As a democratic nation, Samoa has had a stable parliamentary political system since its independence in 1962. For decades, the parliament has been controlled by one political party, the Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP).(21) With little opposition, the HRPP has demonstrated a prolonged commitment to improving and centralizing the health system.(21) However, in 2021 a new political party emerged, Faʻatuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi (FAST), to counter the centralization of government services.(22) FAST now controls the parliament and has focused its efforts on forging new partnerships with private providers in the nation.(22)

6. Role of Government and Market

The interplay of the government and market in the Samoan health system offers insight into the nation’s approach toward achieving universal health coverage. Since its inception, the government has always had primary oversight of the health system. This authority has enabled for the government to offer a wide range of health services as well as create an integrated care system. However, this expansive role of the government has limited the ability for the market to adequately compete and develop. Persistent inefficiencies in the health system have motivated the government to rethink its relationship with the market and consider the development of public-private partnerships.

6.1 Government

The government is the dominant player in the Samoan health system and is responsible for clinical services, pharmaceutical facilities, laboratory testing, medical imaging, public health surveillance, and dental care.(11) The government is thus the major employer of the health workforce and employs a total of 1455 staff including clinicians, administrators, and researchers.(11) The health budget is set on an annual basis by the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance based on the prior year’s budget utilization and performance outcomes for health conditions.(11) The extensive role of the government has enabled for Samoa to develop an integrated health system that efficiently organizes patient records. The Ministry of Health recently rolled-out the National Health ID which provides an identification number for each patient and connects providers to their health records via EMR.(11)

6.2 Market

From 1996 to 2006, Samoa underwent an economic transformation, transitioning from experiencing high budget deficits to attaining macroeconomic stability, embracing free trade, and diminishing the role of government regulations.(23) This transformation resulted in the nation’s highest sustained rate of economic growth.(23) However, following the financial crisis of 2008, the Samoan economy suffered through the next decade due to inefficiencies with state-owned enterprises and government regulations.(23) State-owned enterprises, including the health system, became wasteful and overutilized the limited health resources in the nation. This undercut the ability of the market to compete in the health sector and as a result was unable to formally develop.(23) Recently, Samoa has expressed interest in creating public-private partnerships in the health system to address persistent inefficiencies.(3) These partnerships aim to enhance remote health care access by incentivizing private healthcare providers to work in public rural health facilities.(3)

7. Universal Health Coverage Progress

Over the last decade Samoa has made incremental progress toward achieving universal health coverage. In 2010, the overall UHC Service Coverage Index was 48, but by 2021 it had only slightly improved to 55.(24) This lack of progress is attributed to deficiencies in noncommunicable disease management and service capacity. From 2018 to 2021, Samoa saw a decline in noncommunicable disease coverage from 38 to 34, along with a decrease in service capacity coverage from 65 to 54.(25) Samoa had made promising progress with infectious disease coverage and reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. While these indices have improved to 78 and 64 respectively, there is still a necessity to expand these services to more communities.(24)

7.1 Noncommunicable Diseases

The core deficiencies in Samoa’s noncommunicable disease management stems from high diabetes prevalence and poor hypertension management. In the period of 1978 – 2013, Type II diabetes prevalence in Samoa increased from 1.2% to 19.6% in men and 2.2% to 19.5% in women.(26) This stark increase in diabetes prevalence provides context for Samoa's poor performance of a 23 out of 100 on the mean fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) WHO indicator.(25) A 2018 study revealed that the prevalence of hypertension in Samoan adults was 38.1% and only 10% of men and 29% of women had initiated treatment.(27) This inadequacy in hypertension management sheds light on Samoa's suboptimal score of 52 out of 100 on the WHO indicator for the prevalence of non-raised blood pressure.(25)

7.2 Service Capacity and Access

The limited health workforce in Samoa severely limits the ability of the health system to enhance service capacity and access. Samoa’s 3.65 physicians, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 population is below the WHO minimum threshold of 4.45 per 1,000 population.(20) This is further exacerbated by the deficiency and uneven distribution of physicians, with only 0.48 physicians per 1,000 population, primarily concentrated in two main hospitals.(20) As a result, the Ministry of Health has estimated the health workforce currently requires an additional 252.7 physicians, nurses, and midwives to expand service capacity across the country.(20) This deficiency in providers accentuates the WHO indicator's poor performance, registering 23.6 out of 100 for skilled health professionals density.(25)

8. Reform Proposals

The nation of Samoa faces a variety of health challenges and national constraints, necessitating a comprehensive set of reforms to improve its health infrastructure. The following proposals detail how the nation can leverage both its historical commitment to primary care and current health infrastructure to develop a strong and robust health system.

Reform Proposal 1. Noncommunicable Disease Management: The government should expand the PEN Fa’a Samoa program to increase primary care access to rural communities. Given the rising noncommunicable disease burden, the child and elderly demographic shift, and the high rural population proportion, it is essential that the Samoan government scale up its community health focused programming. PEN Fa’a Samoa has an extensive and established role in Samoan society, having been shaped from the original Komiti Tumamas in the 1920s.(8) The program is only currently available to an estimated 50% of the population, but should be expanded to cover 100%.(3) The government should leverage this deeply ingrained network in order to offer improved access to primary care prevention and treatment services in rural communities.

Reform Proposal 2. Health Workforce Expansion: The government should scale-up its health workforce through educational scholarships, professional development programming, and improved feedback mechanisms. The deficiency in Samoa’s health workforce density and high turnover rate are a major impediment toward achieving universal health coverage.(20) The government should address this shortage at all levels, including health education, professional development, employee retention. Scholarships should be developed to encourage and support students to complete their medical education at local universities such as, NUS School of Medicine (FOM) and Oceania University of Medicine (OUM).(20) Hospital professional development programs should be expanded to allow for providers to enhance their clinical skillsets and capabilities. Retention should be addressed through an annual assessment of salaries and the establishment of an accessible feedback mechanism for staff to report grievances.

Reform Proposal 3. Health Financing Diversification: The government should diversify its health financing strategy through development of public-private partnerships, innovative excise taxes, and a reduction in external aid. The limited ability of the government to finance its health system and estimated 10% increase in population size over the next decade requires the government to diversify its financing mechanism to meet the population demands.(3) The government should develop a public-private partnership with private providers to increase healthcare access in rural communities. This investment into the private sector and decentralization of the health system is politically achievable for it aligns well with the new FAST government’s priorities.(22) Samoa currently has a low excise tax on cigarettes of 49.5% of the retail price and should increase it to the WHO recommended level of 70%.(3) This tax can be earmarked to be used exclusively for health services and improve the government’s ability to finance its health system. Samoa’s dependency on external aid jeopardizes the sustainability and resilience of its healthcare system and should be addressed through the development of a definitive aid completion timeline with strict deadlines for reducing reliance on aid within the nation.

9. Conclusion

Samoa is at a crucial point in its history, tasked with the decision on how it will design a comprehensive, inclusive, and financially sustainable healthcare system. The nation’s dual threat of noncommunicable diseases and limited service capacity is likely to grow in severity with the projected demographic shifts. It is essential that Samoa proactively address its present social, economic, and political constraints in order to best achieve its health priorities. The 1962 independence movement not only ushered in radical change, but also introduced the national motto, Samoa mo Samoa, Samoa for the Samoans. As the government transitions to a more specialized and diversified health system, it is essential that it upholds this maxim and provides access for all Samoans.

References

1. Samoa Data | World Health Organization. Available from: https://data.who.int/countries/882

2. World Health Organization. Samoa - WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2018 -2022. 2023.

3. Ministry of Health. Health Sector Plan. 2019 Jun p. 46.

4. World Bank Open Data [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 21]. World Bank Open Data. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org

5. Oliver D. The Pacific Islands. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1952.

6. Keesing F. Modern Samoa: Its Government and Changing Life. London, UK: G Allen & Unwin Ltd; 1934.

7. Amaama. Mobilising People, Places, and Practice: Public Health Care in Samoa, 1920s to 1950s. Health and History. 2021;23(2):10.

8. Baghirov R, Ah-Ching J, Bollars C. Achieving UHC in Samoa through Revitalizing PHC and Reinvigorating the Role of Village Women Groups. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(1):78–82.

9. Schoeffel P. Dilemmas of modernization in primary health care in Western Samoa. Social Science & Medicine. 1984 Jan 1;19(3):209–16.

10. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). Samoa Health Design. Specialist Health Service; 2018 Jan.

11. Ministry of Health. Annual Report Financial year 2020-2021. Government of Samoa; 2021.

12. United Nations. A/RES/78/4 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 May 4]. Available from: https://www.undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FRES%2F78%2F4&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False

13. Samoa National Health Service. Annual Report Financial Year 2015-2016. 2016.

14. Samoa Family Health Association | IPPF [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 May 4]. Available from: https://www.ippf.org/about-us/member-associations/samoa

15. Ministry of Health. Health Sector Plan 2008-2018. 2007.

16. Global Health Expenditure Database [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 4]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en

17. Ministry of Health. Samoa National Health Account (2014-2015). 2015.

18. Ministry of Health. Samoa National Health Account (2006-2007). 2007.

19. Social Security Administration Research, Statistics, and Policy Analysis [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 4]. Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Asia and the Pacific, 2018 - Samoa. Available from: https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/2018-2019/asia/samoa.html

20. Ministry of Health. Samoa Health Workforce Development Plan 2020-2025. 2020.

21. Hegarty D, Tryon D, Toleafoa A. Politics, Development and Security in Oceania: One Party State- The Samoan Experience [Internet]. ANU Press; 2013 [cited 2024 May 5]. Available from: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/33546

22. FAST [Internet]. [cited 2024 May 5]. Fa’atuatua I Le Atua Samoa Ua Tasi. Available from: https://www.fastparty.ws

23. Bank AD. Reform Renewed: A Private Sector Assessment for Samoa [Internet]. Asian Development Bank; 2015 [cited 2024 May 5]. Available from: https://www.adb.org/documents/reform-renewed-private-sector-assessment-samoa

24. World Health Organization, World Bank Group. Tracking Universal Health Coverage 2023 Global Monitoring Report. 2023.

25. World Health Organization. UHC and SDG Country Profile 2018 Samoa. 2018.

26. Lin S, Naseri T, Linhart C, Morrell S, Taylor R, McGarvey ST, et al. Trends in diabetes and obesity in Samoa over 35 years, 1978-2013. Diabet Med. 2017 May;34(5):654–61.

27. Fraser-Hurt N, Zhang S. Care for Hypertension and Other Chronic Conditions in Samoa: Understanding the Bottlenecks and Closing the Implementation Gaps. World Bank, Washington DC. 2020;